Miami-based architect Bernard Zyscovich has unveiled an expanded, bolder design for his Plan Z, a proposal to create a linear park and network of protected bicycle lanes along the length of the Rickenbacker Causeway to Key Biscayne. They’re calling it Rickenbacker Park.

Tag: Urbanism

Construction Begins on Flagler Street’s Big Redo

Construction began last week on the big renovation of Downtown Miami’s Flagler Street. According to the project’s website “construction fencing was up and in-field mobilization” began on Phase One of the project, the block in front of the Dade County Courthouse, on January 4th. A week later, the road has been ripped up and new sewer/drainage things are lined up, ready to go into place.

Continue reading “Construction Begins on Flagler Street’s Big Redo”

The Many Lives of Miami’s Museum Park

Museum Park – formerly Bicentennial Park – stands adjacent to I-395, Biscayne Boulevard, and Biscayne Bay in Downtown Miami. With neighbors like Herzog & de Meuron-designed Perez Art Museum Miami, the currently-under-construction Patricia and Phillip Museum of Science by Grimshaw Architects and Zaha Hadid’s One Thousand Museum, and the Miami Heat’s American Airlines Arena, Downtown Miami’s Museum Park is one of the centerpieces of a neighborhood transformation. A new Museum Park Conservancy – an organization similar to that of New York’s Central Park – being advocated for by the Miami Foundation with support from the Knight Foundation, could protect and enhance this important place.

Before the Miami Heat or any museum could call this neighborhood home, the long history of creating (and defending) Miami’s urban waterfront was tumultuous and unpredictable. As Miami experienced a tremendous metamorphosis, so did the site that would eventually become Museum Park.

Once a Swamp, Always a Swamp, and Maybe the Next Venice

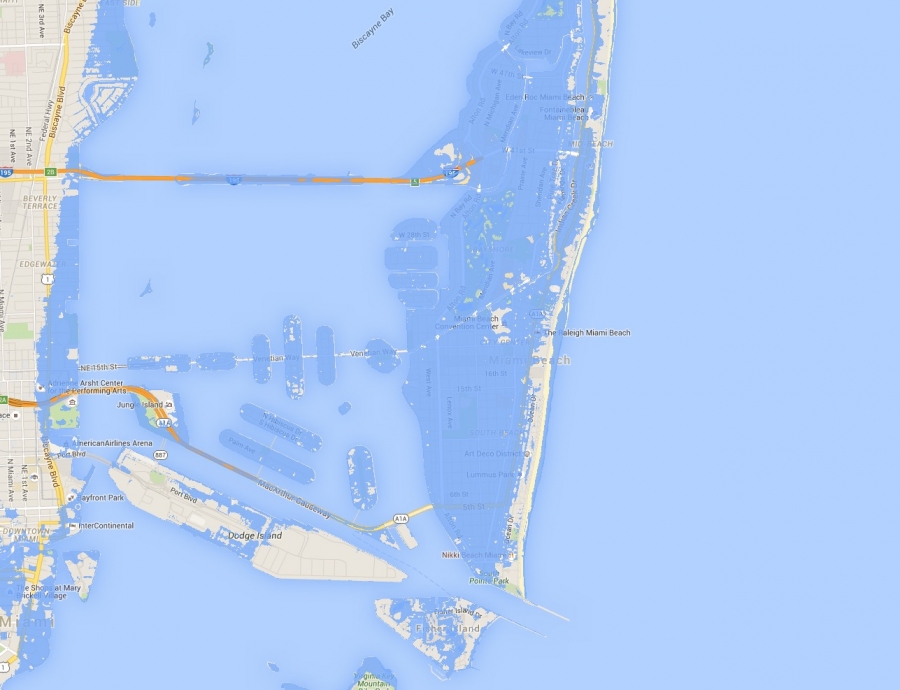

Miami and Miami Beach are chief among coastal cities around the world threatened by sea level rise and its by-now-certain financial and real estate costs. Considering the worldwide implications, all eyes are now on Miami and Miami Beach and their decided courses of action. As stated by Thomas J. LeBlanc, Executive Vice President and Provost of the University of Miami, “we think of Miami as ground zero on climate change. Miami, in some ways, is a model for every coastal city.”

At this point, scientists are generally in agreement that sea levels are rising, but how high and how quickly are the real questions. Recently, on Tom Ashbrook’s show, On Point, Ben Kirtman — a professor at the University of Miami’s Department of Atmospheric Sciences — claimed that the predicted estimates vary between 8 to 24 inches in the next 30 years. Harold Wanless, an expert on sea level rise from the University of Miami who is notoriously pessimistic about South Florida’s future, speculated in a recent Vanity Fair article entitled ‘Waterworld’ that sea levels could rise over 10 feet by 2100, which would cause dire, unfathomable consequences.

According to the World Resources Institute, the two main sources of sea level rise are freshwater input from melting glaciers, ice caps and sheets, and the warming oceans. NASA reports that global sea levels have increased over 6.5 inches in the past century, yet the rate of increase has nearly doubled in the last decade; thus, making it difficult to predict the future of our tides.

South Florida is especially vulnerable as a result of four major factors: the region is flood-prone, hurricane-prone, water-bordered, and uniquely sits atop porous limestone (the “swiss cheese” of rocks as described by Glenn Landers, a Professional Engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers), making the challenge of building for resiliency immense since relatively small sea level increases would still require costly improvements (think more flooding and saltwater intrusion to our drinking water). With Miami regarded as the city with the fourth-largest population vulnerable to sea level rise and the “largest amount of exposed assets” by the World Resources Institute, many would agree it is imperative to plan ahead.

“We think of Miami as ground zero on climate change. Miami, in some ways, is a model for every coastal city.”-Thomas J. LeBlanc

Amidst the concern of rising waters in South Florida is a major real estate boom featuring renowned-architects, sky-high prices, and billions of dollars pouring in, presenting a fundamental paradox. As the recent Vanity Fair article points out, either buyers might not consider these hefty investments as long-term, or their confidence lies in their faith in science and our elected officials. If predictions are remotely accurate, then real estate prices will plunge and all of these investments become duds, not to mention the estimated hikes in flood insurance. At the same time, this real estate boom is helping to boost the City’s tax base, which can in turn mitigate costs to re-engineer its infrastructure.

When Mayor Philip Levine was elected, he pledged to implement solutions for sea level rise. The citywide plan, which includes elevating roads that are below 2.7 feet above sea level, installing 80 pump stations to drain water back out into Biscayne Bay, and raising sea walls, will reportedly cost up to $500 million to stave off the damage of approximately $23 billion of real estate. Even if the pumps are effective, however, the environmental impact is unknown. As the Herald reported, “FIU hydrologist Henry Briceno sent a team to sample water in Biscayne Bay to see whether the mass flushing had any effect. Sample revealed a sixfold increase in pollution in some parts of the bay.”

The solution, albeit knowingly temporary as a way to “buy” time in the hopes of technological advances, is taking shape in Sunset Harbour where the first phase is underway (a controversial issue in itself because Levine owns properties in the area). Prior to construction, the streets notoriously flooded to the point that water would seep into the neighborhood’s storefronts. The city considered the neighborhood’s streets in a state of emergency, which allowed them to circumvent the required public bidding process for the construction’s completion in a timely manner. As the Miami Herald reported, the project began at $2 million in May 2013, and has since reached up to $31 million, which includes extensions to other parts of the city.

Pieces of the neighborhood have been completed, where streets are elevated and stores are sunken. Some streets in the area are currently being torn apart and elevated, while others await construction. The latest test of the elevated streets came during the last king tide, when areas around Miami Beach flooded, and, fortunately, Sunset Harbour remained dry. Passing this trial suggests Miami Beach might be under construction eternally for a long time.

Bruce Mowry, the city engineer for Miami Beach claims “the rising sea levels will continue and street flooding will continue to increase,” reinforcing the need for a comprehensive, innovative solution. This may prove difficult, given that Governor Rick Scott has banned the term “climate change” in his presence (his term of choice? “Nuisance flooding”). Nevertheless, South Florida is banding together in what’s called the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact (Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach Counties). The counties will collaborate in their efforts and strategies to tackle the challenges ahead. Additionally, Miami Beach announced that it will be partnering with Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, which recently announced the opening of its Office for Urbanization. The school will conduct a two-year study of the potential effects and courses of action for Miami Beach.

Governer Scott’s term of choice: “Nuisance flooding.”

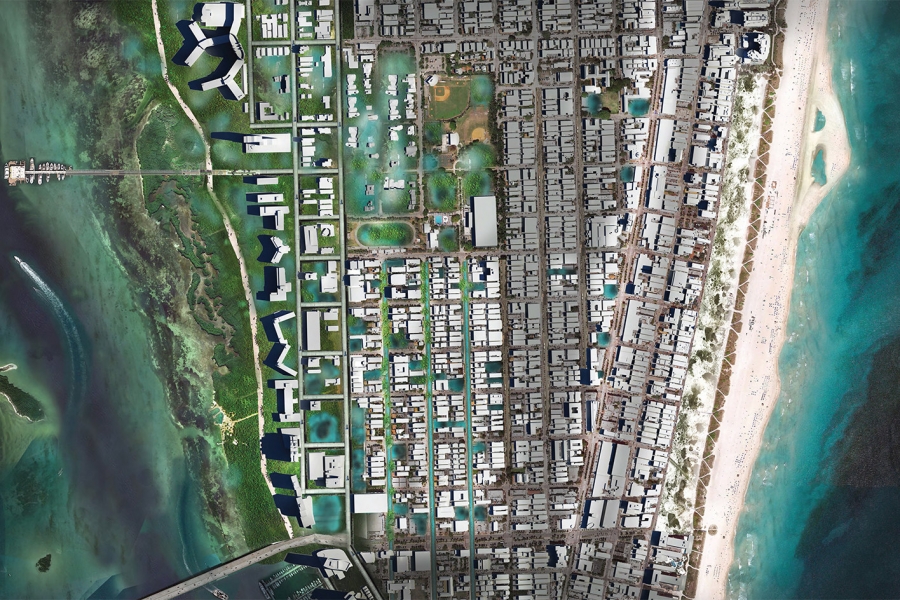

The issue is widely being discussed around the what-ifs and how-tos. The range of scenarios leaves cities guessing how to resolve the matter. Designer Isaac Stein has an adaptive approach mentioned in the Vanity Fair article (the magazine also went into more detail online), replete with Venice-like canals, channels and “washout floors.” A Miami New Times article further delves into Stein’s plan, demonstrating roads to be built upon stilts and reintroducing a mangrove environment, much like what Miami Beach used to be. Stein tells the New Times, “we can either adapt the infrastructure and make space for the water or let it take over.”

During Ashbrook’s On Point show, architect Allan Shulman proposed a similar, Venice-like solution to Stein’s. He suggests a shift towards “living with the water,” utilizing “waterways,” and using parks as “wetland terraces,” or holding beds for water. Shulman goes on to comment that many historically-significant buildings are incapable of being raised, hence why he recommends it may be best to work with the water.

It should be noted that this idea of a “new Venice” is not a new concept for Miami Beach. In the late 70’s, before sea level rise was a thing, developer Stephen Muss hired architect Steven Siskind in an effort to revitalize the then-dilapidated South of Fifth neighborhood (considered as “one of the worst slums in America”). Siskind devised a prescient plan to transform the neighborhood into a “water community” with small islands built around man-made canals. The proposal was ridiculed at the time, but as it turns out, it might be close to our future solution.

Miami Beach is known as a constantly-evolving city and Mayor Levine is hopeful that examples of 21st century innovation can allow for Miami Beach’s survival. Time will tell. In the meantime, what do you say, once a swamp, always a swamp? Are you packing your bags or are you sitting tight?

The Beautiful Simplicity of Miami’s Museum Park

Miami’s Museum Park may be about to undergo a transformation, another twist in the long, rough history of the bayfront park that has the potential to make it an outstanding public space. Of course, in its current simplicity, the park isn’t too bad. Let’s appreciate Museum Park for what it is, while considering what it could be.

Continue reading “The Beautiful Simplicity of Miami’s Museum Park”

How Jugofresh & Its Juice Built a Mini Miami Real Estate Empire

Jugofresh is a homegrown Miami juice bar famously known for their organic, cold-pressed juices that can hit $12 a bottle, smoothies, and health foods. Jugofresh has rapidly expanded throughout South Florida since its outset only three years ago, opening 10 storefronts (several at various Whole Foods supermarkets through a recent partnership), and one new headquarters, with two more stores on the way, and no signs of slowing down. Matthew Sherman, CEO and founder of Jugofresh, was first to Miami’s cold-pressed juice scene, strategically opening his first location in 2012 in the budding Sunset Harbour neighborhood, paving the way for yogis and Flywheel junkies alike.

Jugofresh is more than just a juice bar, however. It’s obvious that above all, the company is selling an experience — from the moment you walk in to the moment you leave and post a photo of your açaí bowl on Instagram (Jugofresh has become so Instagram-worthy, Beyonce couldn’t even resist). Toting around a bottle of juice from Jugofresh has become one of Miami’s “luxury status symbols.” Branding is clearly a major part of their success, all part of the plan to #raisethevibe and to get Miamians to #drinkmadjuice.

The company’s rapid expansion has demonstrated Sherman’s commitment to the company’s branding through savvy real-estate moves and a strict attention to design and detail. It has served to strengthen and reinforce the Jugofresh experience; they are often praised for producing store designs just as fresh as their juices. This achievement can be attributed to Sherman’s dedication to this trademark, making known on several occasions that it’s important for the storefronts to be inviting and mirror the neighborhoods they inhabit. The first store in Sunset Harbour was designed by Allison Almeida, Stephanie Tatum, and Robert Gallagher (founder of Gallagher/AP, and former Vice-President of Interior Design at Oppenheim Architecture + Design) reported Gallagher. In a conversation with Gallagher, he mentioned that the design was mostly “client-driven” with Matthew “playing around with very out-of-the-box concepts” (one being a “theatrical” display of produce and juice-making). The final concept was determined as a “grab-and-go” storefront to accommodate the needs of the urban, dense neighborhood, allowing for ease and efficiency, as well as room for storage.

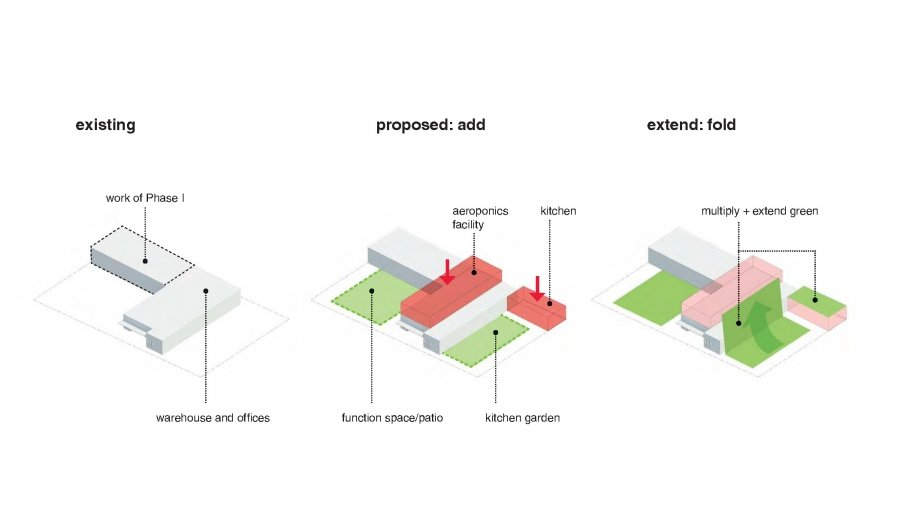

Jugofresh used Architect Allan Shulman and his firm, Shulman + Associates, as the Interior Designer and Architect for their stores in Wynwood, South Beach, and Coral Gables. Their ambitious headquarters in Lemon City, also designed by Shulman + Architects, has recently completed Phase I, which houses a kitchen and their corporate offices. Phase II was to be an elaborately designed 22,000 square foot addition with a hydroponics lab, commercial and juicing kitchens, office space, a 500-square-foot yoga studio, and vertical garden. According to Shulman + Associates, these plans will not come to fruition.

Jugofresh has a “commitment to natural organic materials and high-tech production,” two things that don’t always go together.

As stated on Shulman + Architects’ website, the design for the company concentrates on “transparency as both a way to reveal how the juices are made, and as a way to make the stores more public.” His stores feature reclaimed wood, luxurious white marble, and stainless steel finishes to showcase the “commitment to natural organic materials and high-tech production.” The stores also feature graphic wallpaper by Flavor Paper “used extensively to introduce color and depth, a nod to the complexity and flavor of the company’s juices,” all contributing to a sustainable, cool, clean ambience, pleasing the aesthetically-inclined juice drinker. As for each store, you’ll have to stop by and experience it yourself. Not only is this interesting design-wise, but it’s also a clever marketing strategy.

So, what’s next for Jugofresh? There were reports of a new store opening on 7501 Biscayne Boulevard. Matthew Sherman recently released a statement to The Real Deal, however, indicating that they were unable to dedicate the time and effort to this store. According to The Real Deal, Sherman bought the property in June 2013 for $960,000, and two years later, he sold it to Alexander Karakhanian for $1.4 million, making a solid $440,000 profit. Sherman told The Real Deal that Jugofresh may become a tenant of this property in the future.

Jugofresh’s increasing popularity and heaps of press has turned their stores into destinations, which help to attract residents and tourists to their neighborhoods, arguably paving the way for more commercial investment. With a couple stores opening soon, a fruitful partnership with Whole Foods, and host to many community-wide events, it appears Jugofresh has successfully convinced Miami to #drinkmadjuice.

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates

Jugofresh Headquarters Expansion, by Shulman & Associates