Bjarke Ingels has been called “architecture’s it boy” more than once. He’s young for an architectural superstar, he’s wicked talented, and although he began as a protege of that Patrician of architecture, Rem Koolhaas, Bjarke gleefully seems to turn ‘high architecture’ on its ear. Right now, Ingels is working on a pair of twisty condo towers in Coconut Grove called Grove at Grand Bay, his first Miami project and potentially his first completed project in the Americas. Gridics interviewed him and project developer David Martin when Bjarke was in town to check on the buildings’ progress.

Bjarke Ingels has been called “architecture’s it boy” more than once. He’s young for an architectural superstar, he’s wicked talented, and although he began as a protege of that Patrician of architecture, Rem Koolhaas, Bjarke gleefully seems to turn ‘high architecture’ on its ear. Right now, Ingels is working on a pair of twisty condo towers in Coconut Grove called Grove at Grand Bay, his first Miami project and potentially his first completed project in the Americas. Gridics interviewed him and project developer David Martin of Terra Group when Bjarke was in town to check on the buildings’ progress.

Gridics: Bjarke, Grove at Grand Bay is getting close to completion. Is it in reality what you expected?

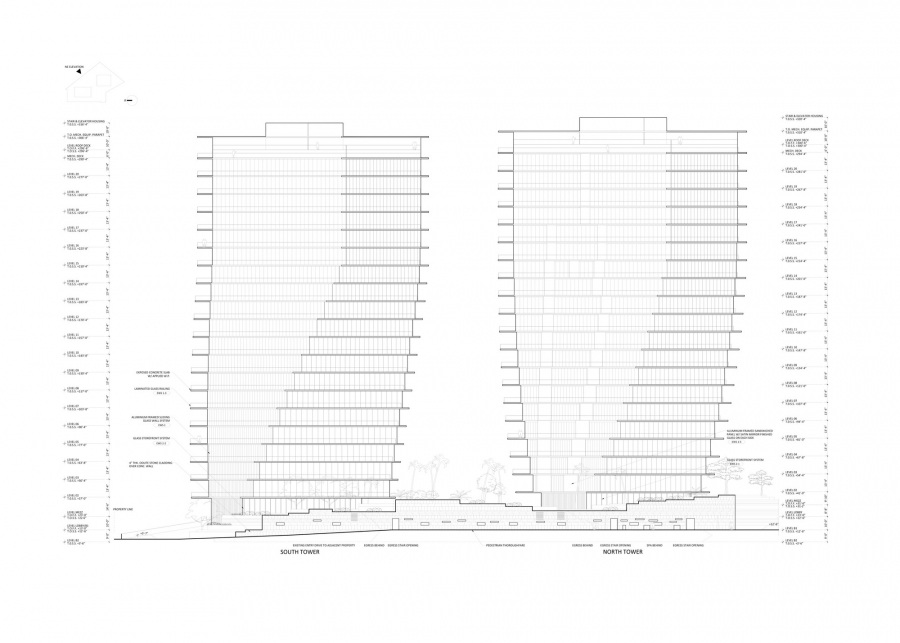

Bjarke: Obviously we’re still a little far from being completely done but one thing you can see is the sort of overall impact of the two volumes and, I think two things:

First, it’s way more dramatic than I thought. The twisting form in the smaller models looked rather subtle and it’s pretty bold in reality. And I think once you sort of sense the heaviness of the material in some of the spaces, like for example in the south tower, in that tall gallery lobby, then you move around the corner and the mezzanine comes in and there’s a column that seems to be almost like forty five degrees, it’s hard to believe how that column is carrying anything. I think it has this expressive sculptural quality that’s more impactful than I could have imagined.

I think what remains to be seen but is happening now is that the oolite walls are coming up really nicely and you can imagine that once nature arrives I think there’s something really special that in a way also is not an architecture that is not super noisy. strangely it doesn’t look alien at all. it’s almost like a local resident but then it has character and personality that’s rather unusual.

David: I don’t think I predicted the impact that this project has had and is going to have on the real estate industry, and on architecture all over the world. I think this is definitely not only a catalyst for Coconut Grove and kind of a revitalization of all the great things about the Grove, but I also think it was a leader in encouraging the industry to strive and work harder and better and take more risk than I think most other developments were doing before this project.

Gridics: That’s a nice segue to my next question. If I have my facts straight this will be your first two completed buildings in the Americas?

David: We’re in a race

Bjarke: It’s going to be neck to neck because West57, in New York, is actually opening up.

David: We were going to be. We still have a chance, but we’re neck in neck.

Gridics: Does this feel like a significant moment to you and does it matter that it happened in Miami?

Bjarke: It’s definitely one of ours. It’s a harmonious tie. I met David for the first time in December 2010. I had just arrived to America, so this became the foundation of our office together with the building we’re doing in New York. And of course it’s incredible to be here now and see how it’s so much a part of the community. And then there’s a story I’ve told about my friend from Miami Ink that I had lunch with that I think shows how there are so many people in Miami that know of these two towers; these two weird twisting towers in Coconut Grove. Both he and his wife lit up when they found out I’m the architect and were like “Don’t tell me that you’re doing those two buildings?!?”

It’s nice when you have a positive impact on a city. I came to Miami for the first time twelve years ago, and since then the transformation that Miami has undergone has made it, along with New York and LA, one of the cultural capitals of the United States. There are neighborhoods like Wynwood and the Design District, the reaccuring arrival of the international art community at Basel, there’s a whole series of events that really makes it one of the cultural capitals of the United States. And of course I think it helps being the capital of Latin America in a way that’s only going to have an increasing impact. I’m very curious, I’m trying to see if I can go to Cuba on this Christmas holiday. In fact, I think it was like a month or so ago that the United States opened their embassy in Havana. So you can imagine that whatever energy that’s coming from that is also going to have a positive influence on Miami.

Gridics: Since Grove at Grand Bay you’ve worked on a number of other projects in South Florida, most of which as you know don’t seem to quite have come to fruition unfortunately, including Lincoln Road, the Convention Center, and Marina Lofts.They all, however had their own unique touches on Miami. Do you have any more projects in the pipeline for South Florida?

David: So, my deal with Bjarke is that I need to find another incredible site because to be honest with you Sean the experience working with Bjarke on this project and the connection and the friendship is something that makes me want to find that special site for him again, and we’ve toyed with a few.

Gridics: For example?

David: A few.

Gridics: Like your house?

David: Haha.

Gridics: You guys have got to have something good enough to replace Ca’ Ziff, the noted postmodernist house that was previously on the site.

Bjarke: I’ve got to say right now our focus is to deliver this baby, Grove at Grand Bay, perfectly and then I think we both want to start the next adventure, but first I think we both want to deliver this baby.

Gridics: But David, you are now building this new family home for yourself, just down the street from Vizcaya. Anything interesting going on there?

David: Not yet. We haven’t decided on an architect yet. My wife and I actually had purchased the penthouse in Grove at Grand Bay and so I think we’re evolving as it relates to what we’re going to do with this penthouse and what we’re going to do with that property but it’s something I want to do that’s special and design driven and that we bring amazing minds like Bjarke’s to execute. At the same time I need to understand that I’m not the only client and that I have my wife and she has as much or more to say about what happens in my house.

Gridics: I’ve heard more, but that’s why you got the house. For the kids, right?

David: Haha. Yes so we have two kids and we want more but the Grove is a special place. It’s somewhere where we intend to raise our family and keep having our company headquarters. So our property is 200 feet wide on Biscayne Bay by 500 feet on Alice Wainwright Park. We have two and a half acres and we have a lot of trees and I think because of that, the landscape architect may be the driver of a lot of the decisions made on the house.

Gridics: Speaking of landscaping and the natural environment, Bjarke, climate change and sea level rise were significant factors in all of your South Florida projects, whether the projects moved forward or not. The projects talked about water in different ways and their relations to it.

Grove at Grand Bay is very much about having views to the water, being elevated above it on the limestone ridge that runs through Coconut Grove, and being connected to it by way of Regatta Park, across the street, which David was instrumental in creating. Marina Lofts was all about its relation to the New River in Fort Lauderdale. Both your masterplans for Lincoln Road and the Miami Beach Convention Center had to tackle sea level rise on low lying Miami Beach.

And your partner at BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), Kai-Uwe Bergmann assisted with the recent sea level rise exhibition at the Miami Center for Architecture and Design, and I think he was an advisor for a University of Florida class dealing with sea level rise in Miami. Your firm is also doing the Big U around New York, to protect that city from sea level rise. Do you have any thoughts about combating sea level rise in Miami. How you might go about that, or not? Would you just let us drown?

Bjarke: I don’t have any specific knowledge on the subject here in Miami. Of course we’re heavily involved in the project in New York, the Big U, or the Dryline as we also call it, where we’re actually in the process of realizing Phase I, which is the East River portion, but I could imagine doing some of the things we’re learning there.

For example, we’re basically trying to match the required engineering with what could be positive environmental and social side effects of that engineering. In the end we won’t just be left with a lot of concrete walls and public utilities, but we’ll actually have public space as a result. You can see how in Europe the old fortresses and walls become where the citizens promenade.

You can see how New York’s Highline, the former train tracks, are one of the city’s most popular parks, so there are already rich, ample inspirations. Brooklyn Bridge Park, is all former docks and quays and piers that are now becoming the parts of the park. What if you don’t have to wait until these purely utilitarian things shut down before you make a nice new thing out of them? What if you make them nice from the get go? In the Grove you can image this. I know David is in some form involved in the waterfront and the new Regatta Park. Maybe if you’re going to plant some flowers and move some dirt anyway, you might as well do it in a way so that it also addresses these issues.

David: So, I was appointed to be on the sea level rise committee at the City of Miami, and I’m not an expert on the topic but I’m trying to learn as much as I can. I think it’s going to take community cooperation and government cooperation to understand some of the zoning requirements in order to deal with the situation.

For instance, as you know, Rene Gonzalez built GLASS, a condo tower in South Beach, for us and he’s been trying to build homes on stilts and learning how that works and gets done. There’s this dogmatic view that says only the new projects have to address sea level requirements. So then what about the existing infrastructure? The more tension this issue is getting from our community, I think the more our leaders are looking to invest. And I think it’s a question of resource allocation. How much money is it going to take to design a solution in every neighborhood? And is it a series of lakes? ‘

One of the unique things that New York has is they have a very strong hard rock base, so a berm can protect the city, whereas in Miami we have a very porous ground, so I think our solutions are going to be a little more creative and technical and require a new way of looking at our green space and parks that we haven’t seen before.

Gridics: Bjarke could be involved in that.

David: As a matter of fact it would be amazing, Bjarke, if at a nominal fee, no I’m joking, my company the Terra Group were to engage you and your firm, based on your experience in New York, to come to a neighborhood here in Miami and try to look at it. I’m sure you have a team for that. To fly them down here and have them look at Miami would be amazing.

Bjarke: This guy, Jeremy Siegel from our office has been entrenched in this for like two years. We have a group that has spent the last two years education themselves in this kind of resilience. And also learning how to facilitate a public outreach process that of course mines specific input and suggestions and concerns from the local neighborhood. As a result they ensure complete local ownership, which is important because these projects are going to have a significant impact on neighborhoods and their access and their relationships to water. So it could quickly be seen as sort of alien interventions chopped down.

This is what we’ve been through the last two years in New York, especially with the population of people that live in New York’s public housing projects, who are very fearful of outside interventions that might drive real estate prices up. They’re quite fearful of any kind of change so they’ve actually been leading, sort of sitting at the table. They embrace the project in an almost unprecedented way.

Gridics: There are a couple things that you said earlier today that I thought were particularly interesting Bjarke, and I wanted to ask you about them. Right. So, obiovusly the shape of Grove at Grand Bay is very distinctive. What other shapes did you consider?

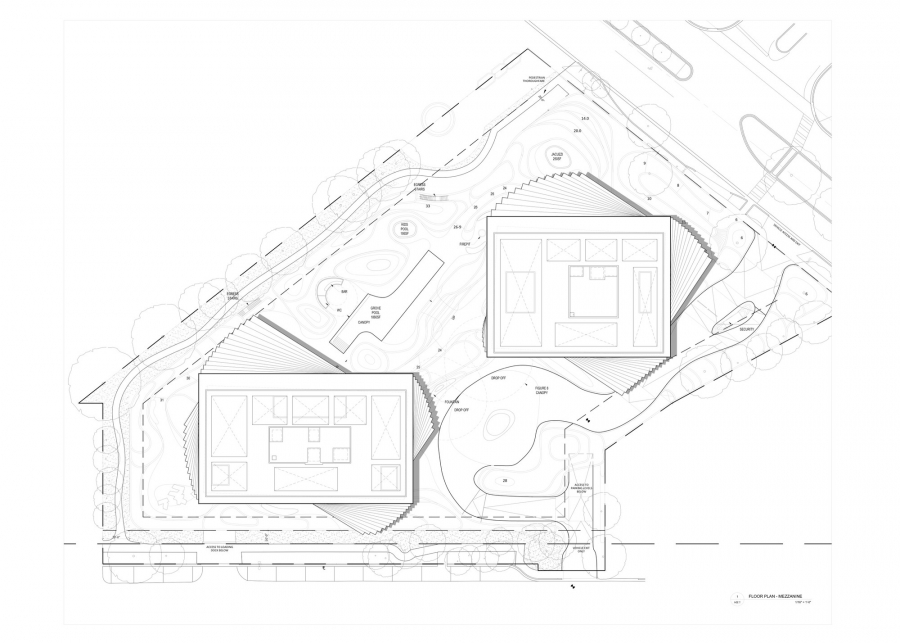

Bjarke: We had a whole little smorgasbord of various ideas. Some of them way too wacky to be able to fit within the constraints of Miami 21. You can see at first it was something completely without reference. Our first conversation as we walked on the roof terrace of the old Grand Bay Hotel, which would be demolished and replaced by Grove at Grand Bay, was to try to come up with something that took more of the precedence of that hotel’s design with its stepped facade. We considered something almost like a man made mountain of individual units.

We toyed for quite a while with this concept we called ‘stacked villas’ where we tried to make four towers with a single unit per floor. Again it became tricky because of the restricted footprint. There was a little too much proximity and at some point, let’s say at halfway through the process, we realized that there was no other way to solve this puzzle than with two buildings.

Then the big question became how to make sure that they are equals and not the privileged and the ‘underprivileged,’ or less privileged. And that’s where the twisting architecture came from.

Gridics: You also said, and this was a great quote, that the buildings have “a few romanticisisms of a Scandinavian’s view of Miami.”

Bjarke: That’s because this our firm’s first in Miami, and I love Miami and I love the architecture and the people. The latino vibe that you get here. In that Scandinavian/Miami sense, I actually own a small portion of a Latin American restaurant in Copenhagen called Llama where we went to town on these mission tiles. So I got to live out my fantasy on that one. But then we have some of the same tiles in the ancillary spaces around the amenities in the bathrooms and the kitchens and the common areas. Together with the plants and the stones we have these.

David: He wanted them in all the elevators.

Bjarke: To have these, ha! David called me up and said “This is your home. If you’re coming home, do you want to go crazy?” I got it out of my system in the smaller spaces.

David: Yeah, you gave in.

Bjarke: I think that Grove at Grand Bay is going to have a very Miami feel, but with the sort of simple Scandinavian sensibility combined. Sort of the warmth of the Latin American with the cool of the Scandinavian.