Museum Park – formerly Bicentennial Park – stands adjacent to I-395, Biscayne Boulevard, and Biscayne Bay in Downtown Miami. With neighbors like Herzog & de Meuron-designed Perez Art Museum Miami, the currently-under-construction Patricia and Phillip Museum of Science by Grimshaw Architects and Zaha Hadid’s One Thousand Museum, and the Miami Heat’s American Airlines Arena, Downtown Miami’s Museum Park is one of the centerpieces of a neighborhood transformation. A new Museum Park Conservancy – an organization similar to that of New York’s Central Park – being advocated for by the Miami Foundation with support from the Knight Foundation, could protect and enhance this important place.

Before the Miami Heat or any museum could call this neighborhood home, the long history of creating (and defending) Miami’s urban waterfront was tumultuous and unpredictable. As Miami experienced a tremendous metamorphosis, so did the site that would eventually become Museum Park.

Museum Park – formerly Bicentennial Park – stands adjacent to I-395, Biscayne Boulevard, and Biscayne Bay in Downtown Miami. With neighbors like Herzog & de Meuron-designed Perez Art Museum Miami, the currently-under-construction Patricia and Phillip Museum of Science by Grimshaw Architects and Zaha Hadid’s One Thousand Museum, and the Miami Heat’s American Airlines Arena, Downtown Miami’s Museum Park is one of the centerpieces of a neighborhood transformation. A new Museum Park Conservancy – an organization similar to that of New York’s Central Park – being advocated for by the Miami Foundation with support from the Knight Foundation, could protect and enhance this important place.

Before the Miami Heat or any museum could call this neighborhood home, the long history of creating (and defending) Miami’s urban waterfront was tumultuous and unpredictable. As Miami experienced a tremendous metamorphosis, so did the site that would eventually become Museum Park.

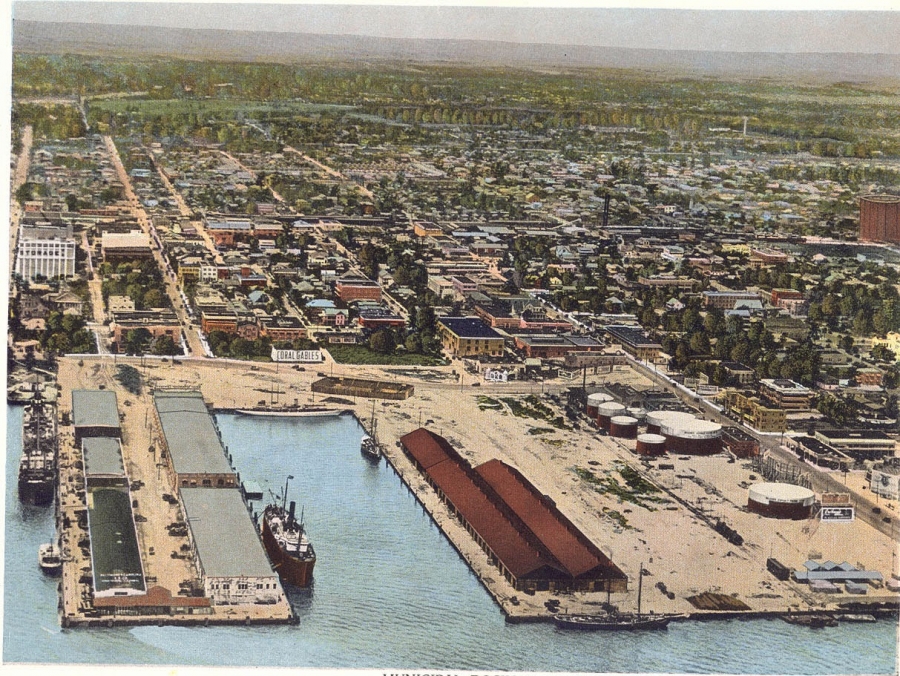

One hundred years ago, except for a few piers, Museum Park was at the bottom of Biscayne Bay. At the end of the 19th century, in Miami’s nascent stages, Henry Flagler – credited as the “Father of Miami” – merged his FEC Steamship Company with Henry B. Plant’s Plant Steamship Company, forming the Peninsular & Occidental Steamship Company. It was at the present location of Museum Park where the company decided to build Miami’s first port along with a Florida East Coast Railway station. The port served as a shipping, cargo, storage, fishing facility, and a submarine chaser school for the United States Atlantic Command (nicknamed the “Donald Duck Navy”) during World War II.

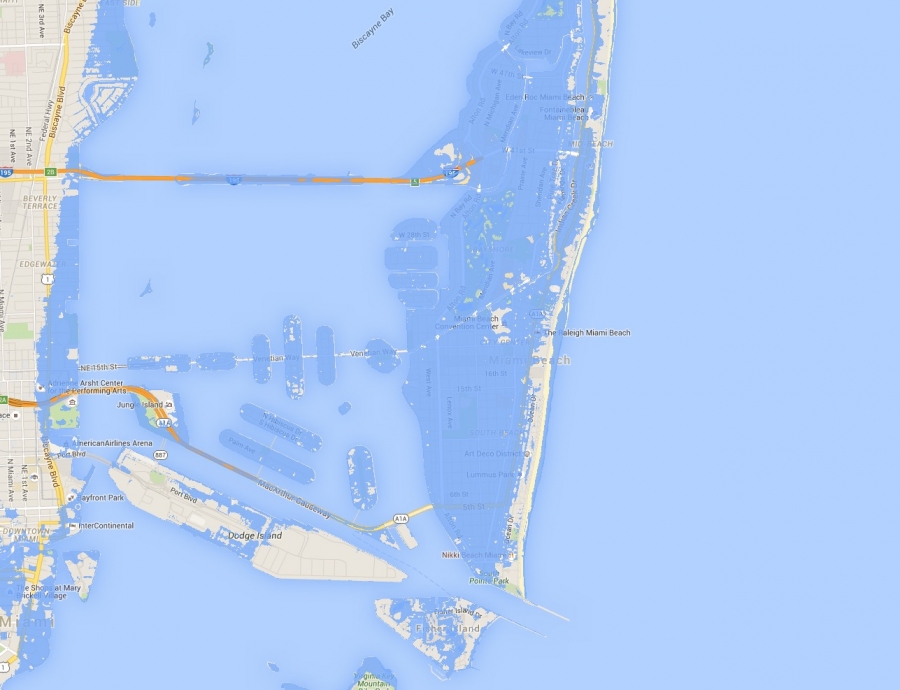

According to Tequesta, the community was angered even then by the poor use of this waterfront site — activists like Frank Walton Chapman and Stobo D’Pass were known for their attempts “to get the port off of Biscayne Boulevard.” Pictures of the site are almost unrecognizable now, seeing as Biscayne Boulevard as we know it – formed the shoreline along Biscayne Bay with piers and wharfs jutting out (the story goes that during low-tide in the early 1900s, before Miami dredged much of its land, you could walk knee-deep across Biscayne Bay from Miami to what would become Miami Beach!). As Miami grew, the city expanded the old port by dredging the bay to create the landfill that would eventually become the park site. The Port of Miami called this its home until the 1960s.

As Miami evolved, the city sought ways to enhance its open space and park opportunities for the community. In an effort to achieve higher standards of recreation, Miami fashioned a master plan (1959) and recreation plan (1960) to add public facilities for residents and tourists, also stressing the importance of neighborhood parks within walking distance of residents (sound familiar?). These two plans sparked momentum for adding to and improving Miami’s public spaces, which led to the implementation of a $10 million plan. This would be particularly crucial in shaping the site as it transitioned from port to park use. At the same time, the need for a bigger, more modern Port became apparent. In 1960, the city commission approved the Port’s relocation to the amalgam of Dodge, Sam’s and Lummus Islands, and the city finally acquired the land where the original port was located.

Following the parks improvement program in the 1960s, activists fought arduously for further parkland improvements. Led by Miami attorney Dan Paul, the parks advocates backed a “Parks for People” bond to issue $40 million that would fund enhancements for 60+ locations. In 1972, the bond passed, providing funding for the development of a large park at the old port site. It was also around this time that Miami was selected by the National Bicentennial Commission to hold a celebration for the country’s 200th birthday in 1976. Thus, in 1974, the city commission approved plans for Bicentennial Park, where the celebration would be held, naming it after the occasion. Unfortunately, Miami was characteristically late to the party, completing the park in 1977. Edward Durrell Stone, the prominent landscape architect, designed the park as an escape from urban living – much like Central Park’s original intent. However, his design called for high walls to enclose the park, sealing off the city and blocking views to the bay. Stone’s intention, although never fully carried out, ended up working against the park’s success as it virtually eliminated linkage to the adjacent neighborhoods. It didn’t help that after the park’s inauguration, several crimes and a murder took place, which further deterred visitors.

As the park fell into decline, the city began to think of ways to spark interest and activate the space. In 1980, the commission endorsed a plan for a maritime museum to be housed at the park. The museum proposal floundered and, in its place, Miami Motorsports Inc. approached the city to use the site as a Grand Prix racetrack, which the City agreed to in 1982. Attempting to stimulate park use, the city also installed a baseball field which was seldom used. By the mid 90s, when the racetrack moved to Homestead, it was clear that the park was failing yet again. Soon after, Bicentennial Park was even court-ordered as a shelter for the homeless. The Biscayne Times later coined it, “the world’s greatest outdoor homeless shelter!”

External forces began to consider Bicentennial Park and the surrounding land as prime real estate: The Port of Miami started a campaign to return port facilities to the park space. Just south of the park site, in the early stages of building the American Airlines Arena in 1996, a team of activists led again by Dan Paul, initiated a protest against the sale of public land for a waterfront arena. The group would become the Urban Environment League (UEL), directed by Jorge Espinel and Dan Paul, an organization whose mandate was to protect Miami-Dade County’s public, historic and natural spaces. Under their direction, the League was able to block the Port of Miami to take over the parkland, although the work was not quite finished.

In 1999, then-Marlins owner, John Henry, announced Bicentennial Park as the perfect location for the new Marlins stadium. A major battle ensued between park activists, the Marlins organization, and commissioners. The Marlins’ Vice Chairman, David Ginsberg, even named the site the “only viable option” for the stadium. The UEL went into full gear: The league organized a series of events, called “Walks of Renewal,” bringing together citizens, activists, and political heavy hitters, which resulted, in 2000, in the hiring of Dover Kohl & Partners to organize a public design charrette. The charrette produced three preferred options: a passive open space, a cultural park with museums, or a mixed use/retail. Dan Paul stepped in to say, “It would be a misuse of an extremely important and valuable waterfront site, important for the future of Miami. There’s no excuse for putting a nonwater-oriented facility on that property.” Luckily, the parks advocates triumphed. In April that year, the City voted in favor of creating a “premier” park. In the meantime, the park was utilized primarily as an event space for Cirque de Soleil, Ultra Music Festival, and Lollapalooza, among others, under the management of the Bayfront Park Management Trust.

A year after conducting a design charrette, the Miami Commission proposed a referendum for $255 million bond, largely issued from Homeland Defense Neighborhood Improvement bond, with $10 million set aside for Bicentennial Park, approved by City voters. In 2002, the “Cultural Park” with the 2 museums option was selected, which resulted in the rebranding of Bicentennial Park into what is now known as Museum Park Miami.

After a public selection process in 2004-2005, the winning team led by Cooper Robertson & Associates and Civitas included Savino & Miller Design Studio as the local landscape architect, Kugler Ning for Lighting, Coastal Systems as the Engineer and Rodriguez and Quiroga Architects as the local architect, to begin a master plan for the new park. Two museums, a bay walk, and a world-class 22-acre park were proposed, cleverly placing the museums along the north edge of the site, which would screen the park from the I-395 highway while allowing for panoramic views of Biscayne Bay and leaving it open and accessible on all sides. In March 2008, the city approved the Master Plan with a $46 million budget, and by 2010, the park was ready for construction.

Can you guess what happened? The Great Recession crippled city finances, halting all plans for the park’s construction. Meanwhile, the two world-class museums as well as new luxury condominium towers across Biscayne Boulevard were under construction and rapidly moving towards opening. The museums were particularly unhappy about the prospect of an abandoned park next to their property and together fought to see the realization of Museum Park. The city felt the need to deliver a park and settled on using the limited funds from the $10 million bond allocation in 2001 to construct a newly-designed open space. Consequently, Coastal Systems and Savino & Miller Design Studio were re-hired to redesign the park to preserve the original design intent and allow for future improvements as per the original plan — and all with $36 million less than initially set aside!

In the midst of the park’s construction, just one month before Museum Park’s opening date, there was yet another obstacle: Beckham. In May 2014, David Beckham and his partners put forth plans to fill in the very last boat slip of the original Port of Miami, known as the FEC Slip, and take over a large portion of Museum Park, for the construction of a Major League soccer stadium between the two museums and American Airlines Arena, a plan that would see the park closed again for years, to be reconfigured, and shrunk even before its opening. With the ensuing press frenzy, the City considered this option, even after investing $10 million into the park, although it was eventually rejected. This was the final green light to conclude the 14-year saga. The opening ceremony for Phase I of Museum Park took place on June 14, 2014.

Through the funds made available, the present Phase I park concept focuses on creating the baywalk and an urban linkage to the museums. The park offers an opportunity to enjoy Miami’s waterfront, providing spectacular views along the half-mile long bay walk, an entry promenade, looping walkways, large shade trees, plazas, open spaces, and rolling lawns, highlighted by two architecturally distinctive museums and four (soon to be five) gleaming white condominium towers. The park is yet to be finished: Phase II of the design will be completed concurrently with the opening of the Frost Museum of Science. One thing is clear, however, in its short life and despite a bare-bones execution, Museum Park has been a success and can only get better with the appropriate support. The park is ripe for the completion of its initial Master Plan, and with community support mounting the conservancy may just be the answer to turning that dream into a reality.